School Metric Guide For School Breaakfast

The purpose of the Breakfast for Learning Education Alliance is to inform our members, affiliates, and networks about the important educational benefits of school breakfast and to promote the broader implementation of proven strategies to increase school breakfast participation, such as breakfast in the classroom. Statement of Support Partner-Developed Resources:.

Co-developed with The American Federation of Teachers (AFT), the “Breakfast Blueprint” is a guide focused on breakfast after the bell programs — such as breakfast in the classroom, “grab and go” breakfast, and second chance breakfast — because they are increasingly popular, are well-researched, and have successfully helped schools and districts improve students’ access to nutritious foods. Co-developed with the National Association of Secondary School Principals (NASSP), this report highlights the experiences of 105 secondary school principals from 67 districts that have integrated breakfast as a part of the school day by implementing a breakfast after the bell program, and provides insights into program benefits and best practices regarding how to launch a similar program. Co-developed with the National Association of Secondary School Principals (NASSP), this toolkit provides guidance to principals in how to effectively partner with their school nutrition department to bring “grab and go” breakfast, second-chance breakfast, or breakfast in the classroom programs to their schools. Co-developed with the National Association of Elementary School Principals, this report provides guidance for principals interested in implementing Breakfast in the Classroom at their schools, and insights into the leadership they can provide to build a strong and sustainable program. Fact Sheet for School Social Workers Co-developed with the School Social Work Association of America (SSWAA), this resource provides school social workers with research and information to advocate for breakfast after the bell programs in their schools.

Fact Sheet for School Nurses Co-developed with the National Association of School Nurses (NASN), this resource provides school nurses with research and information to advocate for breakfast after the bell programs in their schools. Despite benefits generally agreed to be inadequate for a healthy diet through the month, SNAP helps lift millions out of poverty by increasing their purchasing power to afford adequate food. That’s according to the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), an annual report released by the Census Bureau. In September, the Census Bureau released the SPM as well as its report on income and poverty in the U.S., and the U.S. Department of Agriculture published the latest national rates of food insecurity. Collectively, the statistics vividly demonstrate how critical it is to continue to protect SNAP from proposed cuts.

MyPlate Guide To School Breakfast. Last Published:. This infographic highlights healthy foods that are part of a balanced school breakfast. Learn about why eating breakfast is important for learning, and how parents can help their child eat a healthy breakfast at school. [5641f5] - School Metric Guide For School Breaakfast eBooks School Metric Guide For School Breaakfast is available in formats such as PDF, DOC and.

Abstract Objective To determine if a relationship exists between participation in a school breakfast program and measures of psychosocial and academic functioning in school-aged children. Methods Information on participation in a school breakfast program, school record data, and in-depth interviews with parents and children were collected in 1 public school in Philadelphia, Pa, and 2 public schools in Baltimore, Md, prior to the implementation of a universally free (UF) breakfast program and again after the program had been in place for 4 months.

One hundred thirty-three low-income students had complete data before and after the UF breakfast program on school breakfast participation and school-recorded measures, and 85 of these students had complete psychosocial interview data before and after the UF breakfast program. Teacher ratings of behavior before and after the UF breakfast program were available for 76 of these students. Results Schoolwide data showed that prior to the UF breakfast program, 240 (15%) of the 1627 students in the 3 schools were eating a school-supplied breakfast each day. Of the 133 students in the interview sample, 24 (18%) of the students ate a school-supplied breakfast often, 26 (20%) ate a school-supplied breakfast sometimes, and 83 (62%) ate a school-supplied breakfast rarely or never. Prior to the UF breakfast program, students who ate a school-supplied breakfast often or sometimes had significantly higher math scores and significantly lower scores on child-, parent-, and teacher-reported symptom questionnaires than children who ate a school-supplied breakfast rarely or never. At the end of the school term 4 months after the implementation of the UF breakfast program, school-supplied breakfast participation had nearly doubled and 429 (27%) of the 1612 children in the 3 schools were participating in the school breakfast program each day. In the interview sample, almost half of the children had increased their participation.

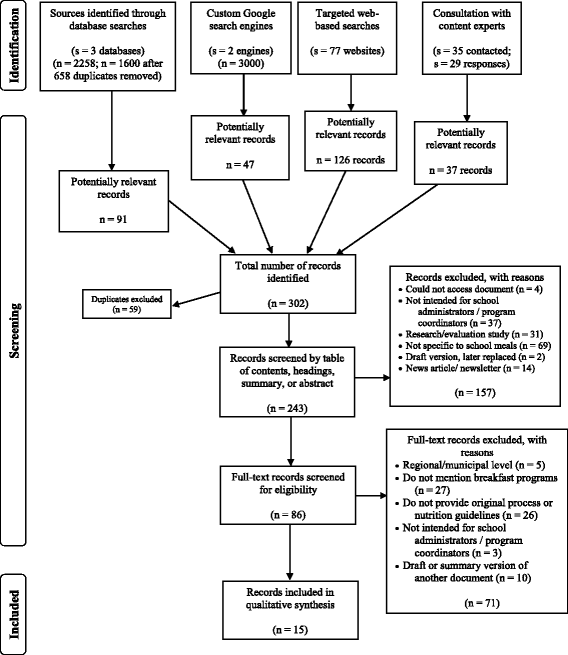

Applying systematic review search methods to the grey literature: a case study examining guidelines for school-based breakfast programs in Canada.

Students who increased their participation in the school breakfast program had significantly greater increases in their math grades and significantly greater decreases in the rates of school absence and tardiness than children whose participation remained the same or decreased. Child and teacher ratings of psychosocial problems also decreased to a significantly greater degree for children with increased participation in the school breakfast program. Conclusion Both cross-sectional and longitudinal data from this study provide strong evidence that higher rates of participation in school breakfast programs are associated in the short-term with improved student functioning on a broad range of psychosocial and academic measures. MANY STUDIES - have demonstrated the negative effects of severe malnutrition on early childhood development and functioning, and a number of reports - have documented that chronic malnutrition negatively affects children's social, emotional, and cognitive functioning. Study population and sampling Data for the current analyses came from a collaborative study of a free breakfast program in the public schools of Philadelphia, Pa, and Baltimore, Md. Students and their parents from 3 inner-city schools (1 in Philadelphia and 2 in Baltimore) were assessed on a variety of academic, psychosocial, and food sufficiency or hunger measures before the start of a UF breakfast program in the schools. In Philadelphia, the school district took advantage of Provision 2 of the US Department of Agriculture school meal guidelines, which permit schools to provide UF meals to all students in low-income areas under certain conditions.

More than 150 other schools had already implemented universal feeding. In Baltimore, a local foundation underwrote the added cost of making school breakfast free to all students who were not covered through standard federal reimbursement. The regular school breakfast was available to all students using the conventional payment categories of free, reduced, and full-price meals during the first semester. At the beginning of the second semester, the same school breakfast that all other students in the school system received was made available for free to all students in these 3 schools. For the present study, students and their parents were interviewed in late January or early February prior to the start of the UF breakfast program and then again in late May to early June after the program had been running for nearly 4 months. In the 3 schools, only children in grade 3 and higher were invited to participate in the study, although all children from all grades were eligible for a free breakfast.

School Metric Guide For School Breakfast

Two schools included kindergarten through sixth grade and the third school included kindergarten through eighth grade. Only students in the third grade and higher were interviewed, since that is the minimum age required for some of the child measures. The parents of all 126 students in the fourth and fifth grades in the Philadelphia school and the parents of all 367 students in the third through eighth grades in the 2 Baltimore schools were invited to participate in the study through letters that were sent home with students. After an additional invitation letter and follow-up phone calls, 220 (45%) of the 493 students agreed to participate. When interviews were scheduled, 51 parents who initially agreed to participate could not be scheduled for an interview, leaving a combined sample of 169 interviews with parents and children before the UF breakfast program (169 77% of the 220 students who agreed to participate and 169 34% of the 493 students in the total sample). Before the UF breakfast program, records of individual student school breakfast participation were available for 79% of the 169 children, resulting in a sample of 133 students with complete parent and/or child measures, school records, and staff reports of participation before the UF breakfast program.

Parents and children were subsequently reinterviewed about 4 months after the initial interviews. In Philadelphia, the parents of 55 of the 59 students who had participated in the initial school breakfast interview were sent invitation letters and were called to set up another interview (4 students had moved).

In Baltimore, because of time and financial constraints, the study design called for only 55 subjects (half of the sample of 110) to be reinterviewed. In these 2 schools, children were randomly sampled from the 3 original breakfast program participation groups (rarely, sometimes, or often) in an effort to match the prevalence rate of participation in the school breakfast program in the reinterview sample. Of the 110 children (55 in Baltimore and 55 in Philadelphia) who were invited for reinterviews, 62 (57%) rarely ate the school breakfast, 30 (27%) ate the school breakfast sometimes, and 18 (16%) ate the school breakfast often. The parents of 102 (93%) of these children agreed to be reinterviewed. When interviews were scheduled, 12 of the parents who initially agreed to participate could not be scheduled, leaving a final post–UF breakfast program interview sample of 90 parents and children (88% of the agreeing sample and 82% of parents who were recontacted). Of these 90 subjects, 5 children (6%) had incomplete post–UF staff-reported breakfast program participation records, resulting in a post–UF breakfast program participation interview sample of 85 parents and children with complete data.

There were no differences in grade level, ethnicity, sex, parental marital status, or fall-term grades between the initial sample and the reinterview sample. In all schools, a variety of informational and promotional methods were used to make parents and children aware of the UF breakfast program and to encourage student participation.

The study was approved by the Subcommittee on Human Studies at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and by the research committees of the Philadelphia and Baltimore public schools. Participation by parents and children was voluntary and access to school records was made possible through separate consent signed by parents and students. Participation before and after the uf school breakfast program School breakfast participation was recorded on site by school cafeteria staff who wrote down the names of all children who took a school breakfast in the cafeteria each day for the week prior to the start of the UF breakfast program (the last week in January or first week in February) and again during the last week in May when the program had been running for almost 4 months. These 2 index weeks were taken as samples of participation before and after the UF school breakfast program. For each student, the school breakfast participation rate was calculated by dividing the number of days the student had taken the breakfast at school divided by the number of days the student was coded as being present at school in the official school record. Children were considered to participate often if they ate breakfast 80% or more of days present. Children were considered to participate sometimes if they ate between 20% and 79% of days present.

Students who ate less than 20% of the time were classified as rarely participating in the school breakfast program. Although we do not know for sure that the students actually ate their breakfasts, the research team observed that most of the students ate most of the components of their meals. While the exact nutritional composition of the meals consumed is not known, all school breakfasts in both school districts were designed by dietitians and had to provide (if they were to be reimbursed by the US Department of Agriculture) nutritionally balanced meals that met the US Department of Agriculture's guidelines on a daily basis.

Meals typically included milk, cereal, bread or a muffin, and fruit or juice. Change in participation after uf school breakfast program The present study used the change in the rate of school breakfast participation (rate at the end of the school term minus the rate at the beginning of the study) as an indication of the change in the consumption of school meals.

Children were classified as increased school breakfast participants if their rates increased by 20% or more over the rate they participated prior to the implementation of the UF breakfast program. Children were considered to have the same school breakfast participation rate if their rates after the UF breakfast program ranged ±19% of their rates before the UF breakfast program.Children were considered to be decreased school breakfast participants if their participation rate declined by 20% or more. Background factors Each child's grade level, ethnicity, sex, and parental marital status were assessed during the initial interviews with parents. Each child's hunger was assessed through the standard 8-item parent questionnaire developed by the CCHIP. The CCHIP scale assesses the child's and the family's experiences of food insufficiency and hunger. When 5 or more indicators are present the child or family is classified as 'hungry.' Positive answers on 1 to 4 questions lead to a classification of 'at risk for hunger,' and families in which there are no yes answers are considered 'not hungry.'

Validity and reliability of the scale have been documented in recent studies. Children's Depression Inventory The Children's Depression Inventory (CDI) is a 27-item questionnaire designed to measure depressive symptoms in school-aged children. It is one of the most widely used depression inventories and has normative data. For each item, children are asked to mark 1 of 3 statements that best describes their behavior and/or feelings during the previous 2 weeks (scored 0, 1, or 2). Total CDI scores were used in the analyses of the relationship between depression and the rates of school breakfast participation. Teacher-reported measures: conners' teacher rating scale-39 For each participating child in the Baltimore subsample, teacher-completed evaluations of child behavior were collected before the UF breakfast program began and again at the end of May. The Conners' Teacher Rating Scale-39 (CTRS-39) is one of the most widely used teacher-reported symptom checklists.

It consists of 39 items that assess hyperactivity and other behavioral problems in school-aged children. Teachers check each item as 'not at all present,' 'just a little present,' 'pretty much present,' or 'very much present' with numerical scoring weights of 0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Although there are 7 subscales on the CTRS-39, the most frequently used scale to assess behavioral problems and the one that is recommended for assessing behavioral change over time is the Hyperactivity Index.

The CTRS-39 Hyperactivity Index is based on a subset of 10 items and has been demonstrated to be a valid and useful assessment tool., Total scores on the CTRS-39 Hyperactivity Index have been shown to correlate reliably with the amount of observed motor activity in the classroom among normal school-aged children as well as ratings of excessive talking. Only the CTRS-39 Hyperactivity Index scores are reported herein because the other scores did not demonstrate statistically significant effects.

For the CTRS-39, RCMAS, CDI, and PSC, higher scores indicate worse functioning. Results Since preliminary analyses showed that the socioeconomic and ethnic characteristics of the children were similar in all 3 schools (all 3 had more than 70% of the students eligible for free or reduced-price meals, and all had more than 70% African American students), the subsamples were combined for all subsequent analyses.

In the combined sample, 384 (78%) of the children were in elementary grades (3-5) and 108 (22%) were in middle school grades (6-8). The mean (SD) age of the sample was 10.3 (1.6) years. Just under half of the sample was male (58 44%) and from single-parent households (60 45%). One hundred-eleven (83%) were from African American backgrounds. There were no statistically significant differences between these groups in terms of rates of participation before the UF school breakfast program. Forty-four (33%) of the children came from families whose parents reported that their children were hungry (13 10%) or at risk for hunger (31 23%) on the CCHIP measure. Background Characteristics Prior to the introduction of the UF breakfast program, the average daily school breakfast participation in the 2 Baltimore schools was 14% (61/432) and 26% (84/322), while in the Philadelphia school the rate was 11% (95/873).

When the data from all the students were pooled, the mean rate of participation before the UF breakfast program for the 3 schools was 15% (240/1627) of days present. Of the 133 students in the study sample, 83 (62%) of the children were classified as eating school breakfast rarely or never, 26 (20%) as eating school breakfast sometimes, and 24 (18%) as eating school breakfast often. Children in the 3 pre–UF breakfast program participation groups did not differ significantly with respect to sex, parental marital status, or race. Hungry and at-risk children were slightly, but not significantly, more likely to participate in the school breakfast program than nonhungry children (57 43% vs 46 35%, respectively). The converse of this finding is that more than half (25 57%) of the hungry or at-risk children participated in school breakfast only rarely or never. In this sample, middle school students were significantly more likely to participate in the school breakfast program compared with elementary school students (13 45% of 29 vs 31 30% of 104) ( z = 3.4; P =.001). Students' grades in math were related to participation in the school breakfast program before the UF breakfast program began, although their grades in science, social studies, and reading were not related.

As shown in, during the fall term prior to the UF breakfast program, children who did not participate in the school breakfast at all or who participated in school breakfast sometimes had significantly lower math grades than those who participated in school breakfast often ( z = 3.4; P =.001). Interview Measures As shown in, the mean child report of depression (CDI) score for children classified as participating in school breakfast rarely was significantly higher (worse; mean, 7.9) than for children who participated in school breakfast sometimes (mean, 4.5) or often (mean, 3.4) ( z= 3.5; P=.001). The mean child report of anxiety (RCMAS) score for children classified as rarely participating in school breakfast (11.4) was significantly higher than the mean for children who participated in school breakfast sometimes (8.3) or often (3.2) ( z= 3.2; P=.001). The mean parent report of psychosocial symptoms (PSC) score for children who rarely ate school breakfast was significantly higher (18.9) than it was for children who ate school breakfast sometimes (14.7) or often (mean, 13.9) ( z= 2.7; P=.007).

After participation in uf school breakfast program Following the implementation of the UF breakfast program, the mean daily school breakfast participation in the 2 Baltimore schools increased to 104 (24%) of 426 and 148 (47%) of 318, while in the Philadelphia school the increase in participation was 177 (20%) of 868. The daily mean for the 3 schools combined rose significantly from 240 (15%) of 1627 students to 429 (27%) of 1612 students (F 2 = 32.5; P. School-Recorded Measures shows the relationship between changes in school breakfast participation and changes in child academic and psychosocial adjustment scores. In the reinterview sample, 56 (42%) of the 133 students increased their school breakfast participation rate, 49 (37%) had the same school breakfast participation rate, and 28 (21%) decreased their school breakfast participation rate. Although these changes in breakfast participation groups in the interview sample did not reach statistical significance, as reported previously, the overall mean school breakfast participation in the 3 schools increased from 15% before to 27% after the UF breakfast program and was statistically significant. Hungry or at-risk children were somewhat more likely to increase their school breakfast participation than nonhungry children (20 46% vs 36 40%), although this difference was not statistically significant ( z = 0.8; P =.40). Absence and Tardy Rates.

Children who increased their rate of school breakfast participation decreased their rate of school absence (−0.1 days) compared with increases of 0.9 days and 1.6 days for students whose breakfast participation rates stayed the same or decreased ( z= 2.6; P=.009). Children who increased their school breakfast participation were also late to school significantly fewer days (−0.4) than children whose school breakfast participation remained the same (+0.3 days tardy) or decreased (+0.9 days tardy); a change that was also statistically significant ( z= 2.5; P=.01). Interview Measures The mean total CDI score decreased by 2.3 points for children who increased their school breakfast participation compared with an increase of 0.6 points for children whose school breakfast participation stayed the same and an increase of 4.6 points on the CDI for children who decreased their school breakfast participation ( z= 2.9; P=.004).

School Metric Guide For School Breakfast Clipart

Children who increased their breakfast participation had significantly greater decreases in total RCMAS score (−4.4 points) compared with children who had the same or decreased school breakfast participation (−0.1 or −2.3 points on the RCMAS, respectively) ( z= 2.0; P. Comment In this study of school breakfast participation in 3 inner-city public schools, fewer than 1 in 5 elementary and middle school children were eating school breakfast prior to the start of a UF school breakfast program, confirming previous reports that the National School Breakfast Program is vastly underused in terms of the numbers of children served and, possibly, its potential to correct some of the negative effects of chronic undernutrition among low-income children in this country. Following the implementation of a UF breakfast program, the present study documented a nearly 100% increase in school breakfast participation and significant gains in academic and emotional functioning for the children whose breakfast participation increased. Before the UF breakfast program, cross-sectional analyses showed that higher levels of school breakfast participation were associated with better performance on a variety of measures of academic and psychosocial functioning in children. Children who ate school breakfast often had significantly higher math grades and significantly lower symptom scores on child-, parent-, and teacher-reported questionnaires than children who ate school breakfast sometimes or rarely.

In the longitudinal follow-up analyses, students who increased their school breakfast participation showed the greatest academic improvements in their math grades, attendance, and punctuality. These children also demonstrated the greatest improvements in functioning on standardized measures of depression and anxiety as reported by students and hyperactivity as reported by teachers. There are a number of limitations in interpreting these findings. First, causal inferences cannot be made since this was not a randomized, controlled study. However, a randomized study, which would ultimately cause some children who were eating breakfast to be deprived of breakfast, is impossible for ethical reasons. Second, the sample size was relatively small and thus susceptible to variations due to chance. Third, the sample may not have been representative because of loss of subjects at various stages in the sampling.

Finally, the children we studied were predominantly African American students from inner-city public school districts, and the impact of school breakfast participation may differ in other racial or ethnic groups from various income levels in other locations. It is possible that the improved psychosocial and academic functioning of the students may be due as much, or more, to an intervening variable as to the increase in the quality or quantity of nutrition per se. For example, it is possible that the observed changes may have been due to factors like the pleasure of increased socialization with peers rather than the improvement in nutrition. Even more plausibly, since in the present sample increased participation in school breakfast is associated with decreased school absence and tardiness, it is possible that improved math grades or decreased depression may be as much a function of increased instructional time as of better nutrition. Although the present sample was too small to permit meaningful analyses, a multiple regression model suggested that both variables (breakfast participation and attendance) were independently associated with improvements in student functioning.

In any case, for the purposes of educational reform, this may be an irrelevant distinction since most educators would probably not care whether the improvements in academic performance and behavior were due to the increase in participation in the school breakfast program directly or indirectly through its capacity to increase attendance. It is also possible that another intervention occurring at the same time may have been responsible for some or all of the observed changes.

The research team was not aware of any special programs operating in the schools and such a situation is less likely given that the improvements occurred in 3 different schools in 2 different districts. Some students may have been in individual interventions like special education or counseling and these interventions, rather than the school breakfast program, may have led to the changes.

Although the present study collected these data on only a subsample of subjects (the Philadelphia students), the relationship of these other interventions to increases in school breakfast participation appeared to be in the opposite direction, with students in counseling or special education less likely (but not significantly) to increase their school breakfast participation. Having noted these potentially confounding factors, the fact remains that these findings are congruent with previous reports of the positive association between school breakfast participation and academic performance., Significant decreases in child absenteeism and tardiness and increases in academic performance were observed in this study as they had been in the study by Meyers et al conducted nearly a decade ago and the more recent report by Cook et al. The students in these earlier reports were from different racial or ethnic groups and geographic locations than the students from the present study. Thus, the association between increases in school breakfast participation and improved school attendance and punctuality has now been replicated across a range of ethnic groups and locations. We have extended the observations made in these earlier studies by documenting for the first time, on an individual basis, a significant relationship between increases in school breakfast participation and decreases in psychosocial symptoms on standardized measures. The decreases found in the reports of children and teachers of psychosocial symptoms in relation to increased school breakfast participation are consistent with and of comparable magnitude to the increases in academic performance.

It remains to be seen if the significant changes in academic, behavioral, and emotional functioning will be sustained for periods longer than the 4 months (1 school term) that the program was in place in our 3 study sites. The associations between school breakfast participation and student functioning appeared to be meaningful as well as statistically significant. For example, in cross-sectional data, the students who ate school breakfast often had math grades that averaged almost a whole letter grade higher than the grades of the students who ate school breakfast rarely (B 3.0 vs C 2.1, respectively), a difference that most educators would probably find meaningful.

In the longitudinal analyses, the observed change was of about the same magnitude (an increase of one third of a letter grade for students who showed an increase vs 1 full-grade decrease for those who decreased their school breakfast participation). Similar associations were observed for the symptom measures reported by children, parents, and teachers. In the cross-sectional data, the symptom scores of students who ate school breakfast rarely ranged from 20% (CTRS-39 Hyperactivity Index) to 100% (CDI) higher than the scores of children who ate school breakfast often.

Differences of this magnitude in psychological measures are generally considered clinically meaningful. In longitudinal data, the differences between students who increased and those who decreased their school breakfast participation were generally smaller, with decreases in mean scores of about 10% to 50%. Most teachers would probably notice such differences, at least regarding behavior in class.

The fact that school breakfast participation was related to parents' reports on the PSC of total numbers of behavioral and emotional problems as well as to students' reports of anxiety (RCMAS) and depression (CDI) and teachers' reports of hyperactivity is in keeping with a recent report, which showed that children's hunger was associated with a general increase of all types of behavioral and emotional symptoms. The present study shows that it is possible to dramatically increase school breakfast participation by making it free to all children. According to 2 studies, it is actually possible to raise school breakfast participation rates to more than 80% (Abell Foundation, unpublished data, 1998; K.

Wahlstrom, PhD, J. Schneider, S.

Reicks, PhD, RD, and J. Labiner, unpublished data, 1996). Additional research already in progress is designed to assess the nutritional content of what students report eating both before and after expansions of school breakfast participation. Physical indicators of nutritional status, such as height, weight, and skinfold thickness, are also being studied in an attempt to tease apart the nutritional vs the social and psychological contribution of school breakfast. For now, however, the present study provides enough data on the positive changes that are associated with major increases in school breakfast participation to suggest that school districts would be wise to study school breakfast expansion as one possible avenue for improving student outcomes. Our study demonstrates not only that substantial increases in school breakfast participation are possible through a universal feeding program, but also that a UF breakfast program can be implemented at little or no cost to the school district for schools with 70% or more of the students eligible for free or reduced-price meals. In these schools, the cost of a UF breakfast program is either free (under Provision 2 billing) or so low (using free, reduced, or paid billing) that local foundations, fund-raising efforts, or the school district itself could cover the federally unreimbursed costs that turn out to be relatively low ($2000-$10 000 per year per school).

From a public health as well as an educational point of view, the potential impact of increasing school breakfast participation through a UF breakfast program deserves much greater attention. This article is also available on our Web site:. Accepted for publication April 6, 1998. From the Child Psychiatry Service (Dr Murphy) and the Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition Unit (Dr Kleinman), Massachusetts General Hospital and the Departments of Psychiatry (Dr Murphy) and Pediatrics (Dr Kleinman), Harvard Medical School, Boston, Mass; the Department of Human Development, Northwestern University, Chicago, Ill (Ms Pagano); the School District of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pa (Ms Nachmani and Mr Sperling); and Baltimore Public Schools, Baltimore, Md (Ms Kane).

This study was made possible through grants from the Kellogg Corporation, Battle Creek, Mich, and the Mid-Atlantic Milk Marketing Association, Towson, Md. In the Baltimore, Md, schools, the Abell Foundation, Baltimore, paid for the federally unreimbursed cost of making breakfast free to all students. The generous cooperation of the Maryland Food Committee, Baltimore, and the participating teachers, students, and parents at the Edmonds, Lakeland, and Barrister Charles Carrol schools are gratefully acknowledged. Tom McGlinchy, Chuck Damianni, and Leonard Smackum, MBA, were instrumental in setting up the study and were major collaborators in this project.

Editor's Note: Here we have more data to prove that your mother was correct about the importance of eating a good breakfast.— Catherine D. DeAngelis, MD Reprints: J. Michael Murphy, EdD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Child Psychiatry Service, Wang Ambulatory Care Center 725, Boston, MA 02114.

Scm 300 class manual. We are constantly scanning and broadening our range of manuals for Bandsaws, CNC Routers, Table Saws, Planers, Sanders, Sawmills, Spindle Moulders etc.